!pip install datasets transformers[torch] evaluate17 Method 3: Hugging Face Trainer API

When we have enough1 labelled data we can step away from SetFit and really utilise the power of LLMs to fine-tune a model using the Hugging Face Trainer API.

The Hugging Face Trainer API is a high-level interface for training and fine-tuning Transformer models. At a high level the process involves:

- Model Selection: Choosing a pre-trained transformer model (e.g., BERT, RoBERTa).

- Data Preparation: Tokenizing and formatting data according to model requirements.

- Configuration: Setting up training parameters and hyperparameters.

- Training Loop: Using the Trainer API to handle the training process.

- Evaluation: Assessing model performance using built-in methods.

The Hugging Face Trainer API simplifies the fine-tuning of large transformer models by abstracts away many of these steps.

Benefits:

- Ease of Use: Simplifies complex training procedures.

- Flexibility: Supports a wide range of models and tasks.

Limitations:

- Computational Resources: Training large models requires significant computational power.

- Complexity: Despite simplifications, understanding underlying mechanics is beneficial.

- Data Requirements: Performs best with larger datasets.

When to Fine-Tune LLMs? * As a rule of thumb, if you have >1k instances of labelled data, it’s worth using a full transformer model and fine-tuning it using the Hugging Face Trainer API

17.1 How to fine-tune a model?

Let’s dive straight into fine-tuning a model using the Hugging Face Trainer API. This section is designed to get you coding quickly. Don’t worry if everything doesn’t make sense right away—focus on running the code, experimenting with changes, and learning by trial and error. It’s okay to break things! The idea here is that learning by doing is the fastest way to grasp new concepts. After this quick walkthrough, you’ll find a more detailed explanation of each step to solidify your understanding, with code that is more suited for a real research project.

So, let’s get started! We will first install the required packages/modules…

… before loading in our dataset. For this example, we’ll use the tweet-eval dataset (from CardiffNLP), which is perfect for sentiment analysis (it’s a bunch of tweets with associated sentiment labels). We’ll also use BERT as our model for fine-tuning.

from datasets import load_dataset

dataset = load_dataset("cardiffnlp/tweet_eval", "sentiment")Before fine-tuning, we need to tokenize the text so that it can be processed by the model. We’ll also pad and truncate the text to ensure all sequences have the same length. This can be done in one step using the map function.

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("google-bert/bert-base-cased")

def tokenize_function(examples):

return tokenizer(examples["text"], padding="max_length", truncation=True)

tokenized_datasets = dataset.map(tokenize_function, batched=True)Since we want to get started quickly, let’s use a smaller subset of the data for training and evaluation to speed things up:

small_train_dataset = tokenized_datasets["train"].shuffle(seed=42).select(range(1000))

small_eval_dataset = tokenized_datasets["test"].shuffle(seed=42).select(range(1000))Now that our data is tokenized, we’re ready to load the model and specify the number of labels (in this case, three: “positive”, “negative”, and “neutral”).

from transformers import AutoModelForSequenceClassification

model = AutoModelForSequenceClassification.from_pretrained("google-bert/bert-base-cased", num_labels = 3)You will see a warning about some of the pretrained weights not being used and some weights being randomly initialized. Don’t worry, this is completely normal! The pretrained head of the BERT model is discarded, and replaced with a randomly initialized classification head. You will fine-tune this new model head on your sequence classification task, transferring the knowledge of the pretrained model to it.

You’ll see a warning about some of the pre-trained weights not being used and others being randomly initialized. Don’t worry—this is expected! The pre-trained head of the BERT model is replaced with a randomly initialized classification head, which we will fine-tune for our sentiment analysis task, transferring the knowledge of the pretrained model to it.

Next we define our TrainingArguments, where you can adjust hyperparameters and training settings. For simplicity, we’ll stick with the default hyperparameters but specify the directory to save checkpoints and the evaluation strategy (which evaluates after each epoch).

from transformers import TrainingArguments

training_args = TrainingArguments(output_dir="./test_trainer", eval_strategy="epoch")How do we know whether training the model is actually making improvements? We need to evaluate it! To evaluate the model during training, we’ll need a function that calculates and reports our chosen metric (in this case, accuracy). We’ll use the evaluate library for this, and define a function called compute_metrics to compute accuracy.

import numpy as np

import evaluate

metric = evaluate.load("accuracy")

def compute_metrics(eval_pred):

logits, labels = eval_pred

predictions = np.argmax(logits, axis=-1)

return metric.compute(predictions=predictions, references=labels)Now, we can bring everything together by creating a Trainer object. This combines the model, training arguments, datasets, and evaluation function for fine-tuning.

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

args=training_args,

train_dataset=small_train_dataset,

eval_dataset=small_eval_dataset,

compute_metrics=compute_metrics,

)Finally, to fine-tune the model, simply call train():

trainer.train()Congratulations! You’ve successfully fine-tuned BERT for sentiment analysis. Feel free to experiment by tweaking the code, trying different parameters, and seeing how the model behaves. It’s all about exploring and understanding what each step does!

17.2 Detailed overview

Now that you have some familiarity with the approach, let’s go into each step in a bit more detail.

Where are we working?

The example code above could be run pretty effectively locally (say in VS Code) because we were not using much training data (remember we took a sample of 1000 posts) and also we were using default hyperparameters (specifically batch size and number of epochs). However, when you come to fine-tune a model for real, we will want more data and more complex training steps, and therefore we will need to be able to utilise GPU within Google Colab. As such, make sure you are connected to a GPU (we recommend T4 as it’s a good balance between speed and cost, whereas A100 is quicker but more expensive).

To use a GPU in Colab, go to Runtime >Change runtime type and select a GPU under the hardware accelerator option

Install the required packages and modules

%%capture

# Install necessary packages

!pip install datasets sentence-transformers transformers[torch] accelerate evaluate

# Imports

from datasets import load_dataset, DatasetDict

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import evaluate

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForSequenceClassification, TrainingArguments, Trainer

import torch

from sklearn.metrics import precision_recall_fscore_support, accuracy_score

from transformers import BertTokenizerLoad in the data

In the example above, we loaded in data that was already saved on the Hugging Face Hub and within the Hugging Face datasets library. However, we can also load in our own data that we have as a .csv file:

dataset = load_dataset('csv', data_files = path/to/csv)By using load_dataset, the dataframe should be read into your environment and be converted into a dataset dictionary (DatasetDict). You can inspect it by running the following command:

datasetThis will output something like:

DatasetDict({

train: Dataset({

features: ['universal_message_id', 'text', 'label'],

num_rows: 10605

})

})You might notice that this looks slightly different from when we loaded the tweet-eval dataset earlier. In the tweet-eval dataset, the DatasetDict included splits for train, validation, and test. However, in our custom dataset, we only have a train split. This is because we haven’t explicitly created additional splits like validation or test, so all our data currently resides under the train key.

There are two ways we can approach this, we can either split up our dataset using train_test_split (which splits into random train and test subsets) or do splitting outside of python (say in R) and read in the already split datasets individually.

*train_test_split method

This method requires you to first split the data into training and testing data, before then further splitting the training data into training and validation. Because of this some maths is required to workout the split proportions.

# Load your dataset (or create one)

dataset = load_dataset('csv', data_files=path/to/csv)

# Split dataset into train (70%) and test+validation (30%)

train_test_split = dataset['train'].train_test_split(test_size=0.3, seed=42)

# Split the remaining 30% into validation (15%) and test (15%)

validation_test_split = train_test_split['test'].train_test_split(test_size=0.5, seed=42)

train_dataset = train_test_split['train'] # 70% of data

validation_dataset = validation_test_split['train'] # 15% of data

test_dataset = validation_test_split['test'] # 15% of data- External splitting

If you have split up the dataset into train, validation, and test splits already, we can read these in individually.

train_dataset = load_dataset('csv', data_files = path/to/csv)

validation_dataset = load_dataset('csv', data_files = path/to/csv)

test_dataset = load_dataset('csv', data_files = path/to/csv)Whichever approach you prefer, you can then bring the individual splits together into a single DatasetDict if needed.

complete_dataset = DatasetDict({

'train': train_dataset['train'],

'test': validation_dataset['train'],

'validation': test_dataset['train']

})Note that by default the dictionary key when you load in a dataset this way is train, which is why for each of train_dataset, validation_dataset and test_dataset are subset by ['train'].

Now is a good time to verify the datasets we have read in

# Verify the datasets

print("Train set:")

print(complete_dataset['train'])

print("Validation set:")

print(complete_dataset['validation'])

print("Test set:")

print(complete_dataset['test'])For the purposes of this more detailed tutorial, let’s again read in the tweet-eval dataset that we will work on:

from datasets import load_dataset

dataset = load_dataset("cardiffnlp/tweet_eval", "sentiment")17.3 Prepare the data

Now we have loaded in the data, let’s prepare it for fine-tuning. Sentiment tasks involve assigning a label (positive, negative, neutral) to a given text. These labels need to be converted into integers for the model to process them. Hugging Face provides a ClassLabel feature to make this mapping easy and consistent:

Step 1: Define Class Names and Convert Labels to Integers

We’ll first define the sentiment class names and use ClassLabel to convert these labels into integers. This ensures that each class (e.g., “positive”) is assigned a specific numeric value. Note from the dataset card we can see the order of the labels (i.e. 0, 1, 2 corresponds to “negative”, “neutral”, and “positive” respectively), so we know what order to assign class_names.

from datasets import ClassLabel

class_names = ["negative", "neutral", "positive"]

# Define the ClassLabel feature

label_feature = ClassLabel(names=class_names)

# Cast the 'label' column to ClassLabel

complete_dataset = complete_dataset.cast_column("label", label_feature)

# Let's verify the mapping and the features of the dataset

features = complete_dataset['train'].features

print(features)Step 2: Verify the Label Mappings

Once we’ve cast the label column to the ClassLabel format, it’s essential to verify that the mapping between the labels and integers is correct. This ensures that the model is trained with consistent and accurate labels.

print(label_feature.int2str(0)) # Should return 'negative'

print(label_feature.int2str(1)) # Should return 'neutral'

print(label_feature.int2str(2)) # Should return 'positive'Step 3: Create and Verify id2label and label2id Mappings

For further robustness, we can explicitly define the mappings between label names and integers using id2label and label2id. This is useful when initializing the model and ensuring consistency across all stages of fine-tuning and inference.

# Create a mapping from integers to labels

id2label = {i: features["label"].int2str(i) for i in range(len(features["label"].names))}

print(id2label) # e.g., {0: 'negative', 1: 'neutral', 2: 'positive'}

# Create the reverse mapping (from labels to integers)

label2id = {v: k for k, v in id2label.items()}

print(label2id) # e.g., {'negative': 0, 'neutral': 1, 'positive': 2}Step 4: Verify the Distribution of Labels in the Dataset

Before proceeding, it’s helpful to check the distribution of labels in the dataset. This helps us understand whether the data is balanced or if certain classes (like “positive”) dominate the dataset.

# Count the number of instances of each label in the dataset

label_distribution = complete_dataset['train'].to_pandas()["label"].value_counts()

print(label_distribution)By checking the label distribution, you can decide if you need to handle any class imbalance issues (e.g., by applying class weights).

17.4 Tokenization

LLMs operate on tokenized text, meaning the raw text needs to be converted into smaller chunks that the model can understand. This is done via a Tokenizer in Hugging Face, and each model will have it’s own Tokenizer.

In addition to breaking down text into a numerical format, tokenization also handles things like:

- Special tokens - The tokenizer adds special tokens such as ([CLS], [SEP]) to the input to help the model further understand the specific structure of the input (e.g. CLS provides signals for when a sequence starts).

- Truncating the input - Transformer models have a maximum input length (512 tokens for BERT). If the input sequence (after tokenization) is longer than this limit, truncation ensures only the first 512 tokens are kept, and the rest are discarded. This can be applied by setting

truncation = True. - Padding text - Transformer models require fixed-length inputs. If sequences are shorter than the maximum length, padding ensures the input matches the required length by adding padding tokens ([PAD]) to the end of the sequence. This can be applied by setting

padding="max_length".

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

# Load the pre-trained tokenizer for BERT via the relevant checkpoint

bert_model_ckpt = "google-bert/bert-base-uncased"

tokenizer_bert = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(bert_model_ckpt)

# Define a tokenization function

def bert_tokenize_text(text):

return tokenizer_bert(text["text"], padding = "max_length", truncation = True)

# Apply tokenization to the dataset

tokenized_dataset = complete_dataset.map(bert_tokenize_text, batched=True)Often times we will find our labelled training data displays class imbalance, where one or more classes are under-represented. This can lead to poor classification performance (often being biased towards the majority class) and give us untrustworthy evaluation metrics.

To address class imbalance, we can adjust the training process to pay more attention to the minority classes. One common approach is to assign class weights, which penalise the model more for making errors on minority classes and less for making errors on majority classes.

Here is a step-by-step guide for calculating class weights and integrating them into the Hugging Face Trainer API.

Step 1: Calculating Class Weights

We first calculate class weights based on the inverse of the class distribution. The idea is to give more weight to underrepresented classes and less to overrepresented classes.

# Calculate class weights based on the distribution of the classes

class_weights = (1 - (complete_dataset['train'].to_pandas()["label"].value_counts().sort_index() / len(complete_dataset['train'].to_pandas()))).values

class_weightsStep 2: Print Class Weights for Verification

Let’s print the class weights and their corresponding class names to verify that everything is correct.

# Print the weights and their corresponding class names

for idx, weight in enumerate(class_weights):

print(f"Class {label_feature.int2str(idx)} (Index {idx}): Weight = {weight}")Step 3: Convert Class Weights to a PyTorch Tensor

Now, we convert the class weights into a format that the Trainer API can use—specifically, a PyTorch tensor.

import torch

# Convert class weights to a PyTorch tensor and move it to the GPU

class_weights = torch.from_numpy(class_weights).float().to("cuda")

class_weightsNote that this is not the only approach to address class imbalance, you could also look at

- Oversampling the minority class

- Undersampling the majority class

- SMOTE (Synethetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) [generate synthetic data]

However, based on our experience, using class weights offers the best balance between time and payoff for our tasks.

17.5 Define metrics for evaluation

Evaluating a fine-tuned model often requires more than just accuracy. We also need metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score to understand how well the model handles different classes.

Please read the corresponding section in the handbook on Model Evaluation for more information on the theory and rationale behind these metrics, and when to chose one over the other.

Just like the example above, we need to define a function (which we will call compute_metrics()) that will enable the calculation of the necessary evaluation metrics. The code below provides per-class metrics and a weighted F1-score (which is useful for handling imbalanced datasets which we often obtain)

from sklearn.metrics import f1_score, precision_recall_fscore_support, accuracy_score

def compute_metrics(eval_pred):

predictions, labels = eval_pred

predictions = np.argmax(predictions, axis=1)

# Calculate precision, recall, and f1 for each label

precision, recall, f1, _ = precision_recall_fscore_support(labels, predictions, average=None, labels=[0, 1, 2])

# Calculate accuracy

accuracy = accuracy_score(labels, predictions)

# Calculate weighted and macro f1 scores

f1_weighted = f1_score(labels, predictions, average='weighted')

f1_macro = f1_score(labels, predictions, average='macro')

# Prepare the metrics dictionary

metrics = {

'accuracy': accuracy,

'f1_weighted': f1_weighted,

'f1_macro': f1_macro

}

class_names = ["negative", "neutral", "positive"]

for i, label in enumerate(class_names):

metrics[f'precision_{label}'] = precision[i]

metrics[f'recall_{label}'] = recall[i]

metrics[f'f1_{label}'] = f1[i]

return metricsWhilst this looks like overkill, and probably is for what you present to a client when reporting evaluation metrics, having all of this information when understanding model performance is extremely useful- it is better to have too much information here than too little.

17.6 Instantiate the Trainer

Now we have loaded in our data, prepared it for fine-tuning, and created our function for model evaluation, it is time to load in the model we will be fine-tuning and instantiate our Trainer.

Let’s start by loading in the pre-trained BERT model:

model = AutoModelForSequenceClassification.from_pretrained(bert_model_ckpt, num_labels=len(class_names), id2label = id2label, label2id = label2id)But what does this actually do or mean?

AutoModelForSequenceClassification: is a class from thetransformerslibrary. It’s a pre-defined architecture that uses the pre-trained model and adds a classification head (a fully connected layer) on top of it. The classification head is responsible for predicting which class a piece of text belongs to. Note BERT models actually have a synonymous class calledBertForSequenceClassification, however usingAutoModelForSequenceClassificationmeans we could in theory swap outbert_model_ckptfor another transformer model (note thisbert_model_ckptcomes from our tokenization step).from_pretrained(model_name): this method loads a pre-trained version of the model. Remember we are not training a deep neural network from scratch- we’re leveraging a pre-trained model that already understands language structures.num_labels=len(class_names): this specifies the number of classes or categories that the model needs to classify text into.num_labelsensures that the final layer of the model has the correct number of outputs corresponding to the number of possible classes.id2label = id2label&label2id = label2id: ensures consistent handling of labels in the model- this makes it much easier to understand the predictions as they can be translated between integers and labels (rather than just integers).

And then we set up the training arguments by creating a TrainingArguments class which contains all the hyperparameters you can tune as well:

training_args = TrainingArguments(output_dir = "./results",

num_train_epochs = 5,

learning_rate = 1e-5,

per_device_train_batch_size = 16,

per_device_eval_batch_size = 16,

weight_decay = 0.01,

warmup_steps = 600,

eval_strategy = "epoch",

save_strategy = "epoch",

logging_steps = 100,

logging_dir = "./logs",

fp16 = True,

load_best_model_at_end = True,

metric_for_best_model = "eval_loss",

push_to_hub = False)Let’s go through each of these hyperparameters/arguments step by step, explaining what they are and how we can choose an appropriate value (where relevant)

output_dir: Directory where model checkpoints and training outputs will be saved.num_train_epochs: Specifies the number of complete passes through the training dataset (an epoch). We find that fewer epochs (1-3) are suitable for fine-tuning when you’re only adjusting the final classification head, or if the model is large and already well-trained. More epochs (5-10) may be needed when we’re training with less data or starting with a less well-trained pre-trained model. We can implement “early stopping” so that if the model starts to drop in performance after a certain number of epochs, training halts to avoid overfitting.learning_rate: Controls how much to change the model in response to the estimated error each time the model weights are updated. Smaller values such as 1e-5 and 1e-6 are preferred when fine-tuning an entire model or working with a large dataset, as it ensures more gradual learning (a higher learning rate could destroy the pre-learned features). However, if you are only tuning the final classification head (while keeping other layers froze), you can use higher learning rates such as 1e-3, as it allows the model to adjust faster.per_device_train_batch_size: Sets the batch size, which is the number of samples processed before the model updates its weights during training. Larger batch sizes (e.g., 32, 64) lead to faster training but require more memory (RAM) and may lead to poorer model performance at generalising over unseen data. Smaller batch sizes (e.g. 8, 16) are slower but can help when memory is limited or for more stable training, however if it is too small the gradient estimation will be noisy and not converge. In our use cases 16 or 32 tends to work fine.per_device_train_batch_size: Sets the batch size for evaluation (validation) on each device. Best to keep it to the same as theper_device_train_batch_size.weight_decay: Weight decay is a regularisation technique that helps prevent overfitting by penalizing large weights in the model. It reduces the model’s complexity, and values around 0.01 are common. If you notice overfitting it might be worth trying larger values (e.g. 0.1) or if you notice underfitting it might be worth smaller values (e.g. 0.001 or even 0).warmup_steps: These gradually increase the learning rate at the beginning of training before settling at the specified rate. This helps stabilise training and prevents the model from making large adjustments too early. Typically you might want to set this as ~10% of the total training steps, though 600 isn’t too bad.eval_strategy: Specifies when to run evaluation (validation) on the dataset during training. The values this hyperparameter can take areepoch(runs evaluation at the end of each epoch- common for most training tasks),steps(runs evaluation at a set number of steps, which is sometimes useful for longer training runs or when training for many epochs), orno(don’t evaluate- do not chose this!). We find thatepochis usually sufficient, but recommend tryingstepstoo if you’d like more control over evaluation visualisations.save_strategy: Specifies when to save the model checkpoint. Similar toeval_strategythe argument takesepoch(saves a model checkpoint at the end of every epoch- which is ideal for most fine-tuning tasks) orsteps(saves checkpoints every set number of steps, useful for longer training runs).logging_steps: Specifies how often (in terms of steps) to log training information such as loss. Smaller values (e.g. 10-50 steps) provide more frequent updates by may slow down training due to excessive logging, whereas larger values (e.g. 200-500 steps) provide less frequent updates but are useful for faster training. We would suggest 100 steps is a balanced choice, giving regular feedback without overwhelming the logs.logging_dir: Directory where logs are savedfp16: This boolean enables mixed precision training using 16-bit floating point (FP16) arithmetic. This speeds up training and reduces memory usage without sacrificing model performance.load_best_model_at_end: Automatically loads the best model (based on the evaluation metric) after training completes. We would have this astrue.metric_for_best_model: Specifies the evaluation metric used to determine which model is “best” during training.eval_lossis common for classification tasks, and therefore in conjunction withload_best_model_at_endit means the model with the lowest validation loss will be saved. You can also specify other metrics like accuracy, F1-score, precision, etc., depending on your task and what is most important for evaluation.push_to_hub: Determines whether the model and results shoul dbe uploaded to the Hugging Face Hub.

Now, finally, we can instantiate our Trainer. Here we provide our Trainer class all the information required to train and evaluate the model, namely the model itself, the training arguments, the training dataset, the validation dataset, and the function to compute evaluation metrics

trainer = Trainer(

model = model, # The pre-trained model

args = training_args, # Training arguments

train_dataset = tokenized_dataset['train'], # Training dataset

eval_dataset = tokenized_dataset['validation'], # Evaluation dataset

compute_metrics = compute_metrics, # Custom metrics

)Now our Trainer is instantiated (as trainer), we can call the trainer and train it using train(). Note that this will take quite a while (~20/30 mins) even on a GPU as we are training on

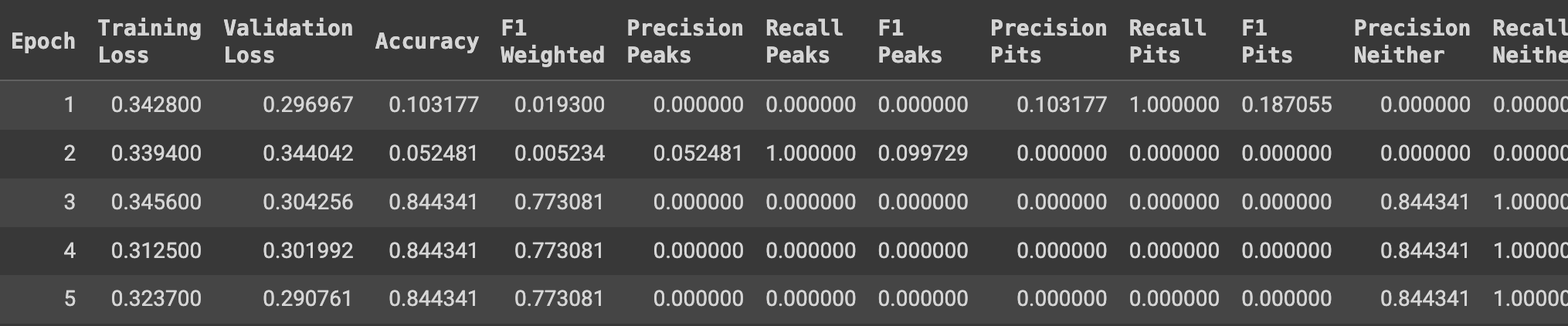

trainer.train()Now, depending on our training arguments, you will see an output printed after every epoch or n steps, which shows our evaluation metrics as below

17.7 Model evaluation

After training, we can evaluate the model on the validation set:

trainer.evaluate()This will provide the evaluation metrics defined earlier for our best performing model.

Finally, once we are happy with our model (See Model Evaluation page first!), we may want to evaluate the model on the held out test dataset. It is these values that we would report when reporting final model performance.

test_metrics = trainer.evaluate(tokenized_dataset['test'])

test_metricsSee the page on data labelling for our advice on knowing when you have “enough” - spoiler, it’s difficult↩︎